Thomas Nast: His Period and His Pictures by Albert Bigelow Paine. Published by The Macmillan Company, New York and London in 1904. 583 pages and over 425 illustrations. Available via Google Books.

This is part four of a series of posts about Paine's biography of the caricaturist Thomas Nast and research I did spurred on by reading the book. - DonkeyHotey

As 1866 begins, Thomas Nast is a successful artist made famous by passion, work ethic, Harper's Weekly and the Civil War. He busies himself producing illustrations for Harper's Bazaar, various book projects and unsigned caricatures for a comic paper, Phunny Phellow (alt) and other publications. The comic paper is presumably the Comic Monthly.

What follows is a contemporary description of unknown bias of the Phunny Phellow from Trübner's American and Oriental literary record: a monthly ..., Volumes 1-24. September 21, 1865

“Phunny Phellow is a monthly folio sheet of 16 pages, published in New York, and now in its eighth volume, -- its original illustrations are large in size, but very small in wit; its best illustrations are copied from Punch, but in execution lack the finish of our old friend, - Frank Leslie's Budget of Fun, which has reached its 91st monthly issue, is a large folio of 16 pages.” - Page 118

Here is another piece about the Phunny Phellow and the Comic Monthly from A History of American Magazines: 1850-1865 by Frank Luther Mott that I believe was published in 1938.

“... the Comic Monthly, published 1859-81 by J. C. Haney at seventy-five cents a year and later by Jesse Haney at somewhat higher prices; and the Phunny Phellow, issued 1859-76 by Okie, Dayton & Jones at sixty cents a year. Later, Ross & Tousey were distributors of Phunny Phellow, while Street & Smith appear to have owned it. To both these cheap papers, Nast contributed drawings - to the former in 1860 and to the later in 1866. Bellow and Beard were leading Comic Monthly artists. Phunny Phellow practically filled eight of its sixteen pages with woodcuts. It was a phree borrower of phoolery; consequently its jokes were not so bad as its cuts.”

There is some mystery about how many unsigned images Thomas Nast produced for Phunny Phellow and other publications. No specific numbers are given by Paine. He appears to have done it for cash and to have other outlets for ideas and experimentation.

In April of 1866 Max Maretzek produced the “Bal d'Opera” at the old Academy of Music in New York City. The event featured sixty life size Thomas Nast caricatures (alt) of prominent people ringing the room. An illustration was published in Harper's Weekly on April 14, 1866 featuring all the caricatures and a representation of the ball room. The caption under the two page spread is “Grand Masquerade Ball Given By Mr, Maretzek at the Academy of Music, April 5, 1866 - By Thomas Nast (See Page 234)” The announcement in the New York Times was titled, "Maretzek's Bal d'Opera" and described arrangements for the “great event of the season.” The individual caricatures were later sold at auction.

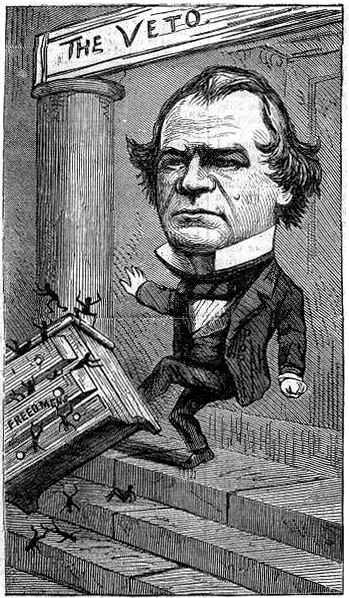

Nast's distaste for Andy Johnson grew. The two page feature titled “Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction and How it Works” (alt), is described by Paine as the “high water mark for 1866” and presented Johnson as Shakespeare’s Iago. Nast poked “Andy” by presenting him as a bully, “King Andy” (alt), “St. Andy” and by associating him with Ku-Klux-Klan. His cartoons of Johnson are considered a major shift in style towards caricature. The pallet cleanser for all this heart wrenching disappointment was “Santa Claus and His Works” (alt) that appeared in the December 25, 1866 issue of Harper's Weekly.

The first cartoon in Nast's campaign to expose graft in New York titled “Government of the City of New York” (Ebay search) was published on February 9, 1867. Paine describes this first shot across the bow of Tammany.

“There were no individual faces in this first picture. It merely showed the City Government in the hands of a corrupt element, roughs and gamblers, with the "Steal Ring" suspended behind the chair of the chief officer. It was by no means an able effort as compared with the " Ring " cartoons which were to appear a few years later; but if we except the page of "Police Scandal" in 1859, it was the earliest of Nast's "corruption" cartoons, and constituted a sort of manifesto of a future crusade.” - page 114

Reconstruction and the aftermath of the bloody war continued to be the nation's obsession in 1867. Two powerful illustrations not mentioned in the biography are “Slavery is dead(?)” (alt) published on January 12, and “We Accept the Situation” (alt) on April 13. This shows a slave being sold before the Emancipation Proclamation and an African-American being whipped under States Rights in 1866. Nast points his pencil at the KKK and other aspects of Reconstruction. The outstanding Reconstruction pictorial for this year was “Amphitheatrum Johnsonianum” (alt).

Paine also does not mention another image the cartoonist produced titled “The Day We Celebrate” (alt1) (alt2) and published on April 6, 1867. The representation of Irish people as simian thugs, along with other Nast cartoons, are still stirring controversy today. There are a few cartoons scattered through the book that touch on issues of race and religion, but there appears to be many more that were not included. For this reason I am going to ignore the few examples that are included and address these topics as a followup post.

The later half of 1867 was taken up with book projects and working on paintings for the “Grand Caricaturama” that would debut in December. He produced thirty-three panels about nine feet high and twelve feet wide. This project was inspired by the success of the “Opera Ball” mentioned in a previous post. Unfortunately the “Caricaturama” was an artistic hit, but a financial flop. The presentation on stage was just not appreciated enough. HarpWeek has an excellent collection of images and information about the “Grand Caricaturama” they call “Nast On Broadway: His Grand Caricaturama of 1868”. This site features detailed descriptions of the project including separate pages of each of the images featured in the show. This is in two sections: “From Independence to the Civil War” and “Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction Era”. Be sure and read the section titled “The Fate of the Caricaturama Panels” to find out why only a few of the original panels survived. Read this 1868 review of the Caricaturama published in the edition of Putnam's Magazine Vol. 1 for a contemporary perspective.

The Grand Caricaturist was a featured artist at the launch of The Chicago Illustrated News which only published for a few months. You can view a cover of The Chicago Illustrated News at the Magazine History: A Collector's Blog (alt). There is an image that appeared in the News available in The Annotated Christmas Carol: A Christmas Carol in Prose With the caption, “'Mr. C-----S D----S and the Honest Little Boy' Cartoon by Thomas Nast, The Illustrated Chicago News, April 24, 1868. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.” This advertisement appeared in The Nation an April 3, 1868 announcing the venture:

The First Number of new ILLUSTRATED CHICAGO NEWS will be for sale in this city on Thursday April 23. A CAPITAL NUMBER CARTOONS BY THOMAS NAST. A Serial entitled “The Fenways” by J. T. Trowbridge and several other excellent features. FARNUM & CHURCH, Publishers, 42 Sherman Street, Chicago, Ill. Trade supplied by the American News Agents for the Publishers.

The artist turned partisan showman prepares backdrops for the Republican Convention in Chicago on May 20. When it was announced that Grant was the Convention's unanimous choice, a curtain lifted revealing the image challenging the Democrats to “Match Him” or match Grant. This idea was used as the theme for a cartoon later in the campaign. “Match Him” became the catch phrase for the campaign. There was even a song with that title with sheet music and lyrics. “Grant the hero's on the course; Match him, match him...”

After the convention, Nast began contributing again to Harper's Weekly. Paine describes little of the artist's process, but he shares the facts that Nast had a studio behind his home on 125th Street in Harlem. There Mrs. Nast (Sallie) would read newspapers and fiction to him while he worked and help him with the text in his cartoons. He would also employ college students to read and discuss science and history. Nast read the newspapers constantly and collected clippings on which he would pencil comments in the margins. According to the biographer, Nast came up with his own ideas for his entire career. He did not accept ideas from friends and admirers other than Mrs. Nast. He seemed particularly adverse to advice from Harper's editor George William Curtis. They were frequently at odds. It appears the cartoonist discussed issues with people, but shied away from specific suggestions. Paine provides this quote from Curtis:

“The pictures you suggest are, as usual, telling arguments and hard hits,” he says. “Some of them are so hard that I hope it may not be necessary to use them.” - Page 123

Later in the narrative it is revealed that the Caricaturist changes the way he creates his work. “Not Love, But Justice”, published June 26, 1869, is the first cartoon where Nast perfected using a pencil to draw his work on engraving blocks. Paine wrote:

“Drawings for illustration were still made on wood blocks and engraved by hand. Most of Nast's earlier work had been done with fluid color, washed in with a brush. In the 'Not Love but Justice' above mentioned, the artist, inspired by a masterly drawing in London Punch, discarded the brush and used his pencil with a care and insight scarcely comprehended before.” - Page 135

His method of work changes again in 1880. Chemical process reproduction technology replaced hand engraved wood block. Nast had to adjust to creating his work with pen and ink on paper. Previously he used soft pencil to draw the image in reverse on hard boxwood blocks. It took Nast many months to adapt to the new approach and gave critics a chance to suggest he was losing touch.

The biography is thin on facts about Nast's creative process, studio and work habits. It is clear that he was always sketching, discussing politics, and devoting many hours on projects. He worked with pencil, brush, crayon and pen. Mrs. Nast would model for him. Many of his visual ideas came from literature and mythology via books, museums, galleries, artwork, and architecture. He created likenesses using photographs from many sources including his subjects. Politicians were very anxious that Nast had a photo of them that would help him accurately represent them. He would meet his subjects in person at his New Jersey home, in New York and during his travels. The sketches he made in the field seem to be very cryptic, almost a short hand. The sketches would give him the basic idea of the position of elements, perspective, lighting, and suggestions of shapes. I will look for other sources to add a followup post on this topic.

The next post will begin with the campaign of 1868 and covers the battle with Boss Tweed.

NEXT - Thomas Nast 5